On Sunday, June 15, The Cheech Marin Center for Chicano Art & Culture in downtown Riverside celebrated its third anniversary with the unveiling of “Cheech Collects IV,” the latest iteration of its annual exhibit showcasing new acquisitions and never-before-seen works. More than just a cultural celebration, the event emerged as a powerful counterpoint to the tense political moment unfolding across the country, where a wave of immigration raids and militarized crackdowns on protests have struck fear across Latino communities.

As demonstrators marched and chanted across California and beyond, The Cheech became a space of reflection, resilience, and collective affirmation—a visual archive of struggle and survival. In a time when immigrant families are being torn apart, this exhibit offered a different kind of visibility: one rooted not in headlines, but in the enduring creativity and contribution of the very communities under attack.

The exhibition is divided into five thematic sections, each offering a distinct lens into the depth and diversity of Chicano art.

The first section spotlights the work of Wayne Alaniz Healy, the show’s inaugural featured artist and one of the most respected figures of the Chicano art movement. Among the highlights is An Afternoon in Meoqui, a neon-colored celebration of community, where tacos, beans, and tamales anchor a vibrant neighborhood scene.

Healy, cofounder of the East Los Streetscapers collective alongside David Botello, helped redefine public art in Los Angeles through socially conscious murals that instilled cultural pride across communities. Botello’s own work is also featured, including Wedding Photos–Hollenbeck Park, a dreamlike composition rendered in rich hues of green and blue.

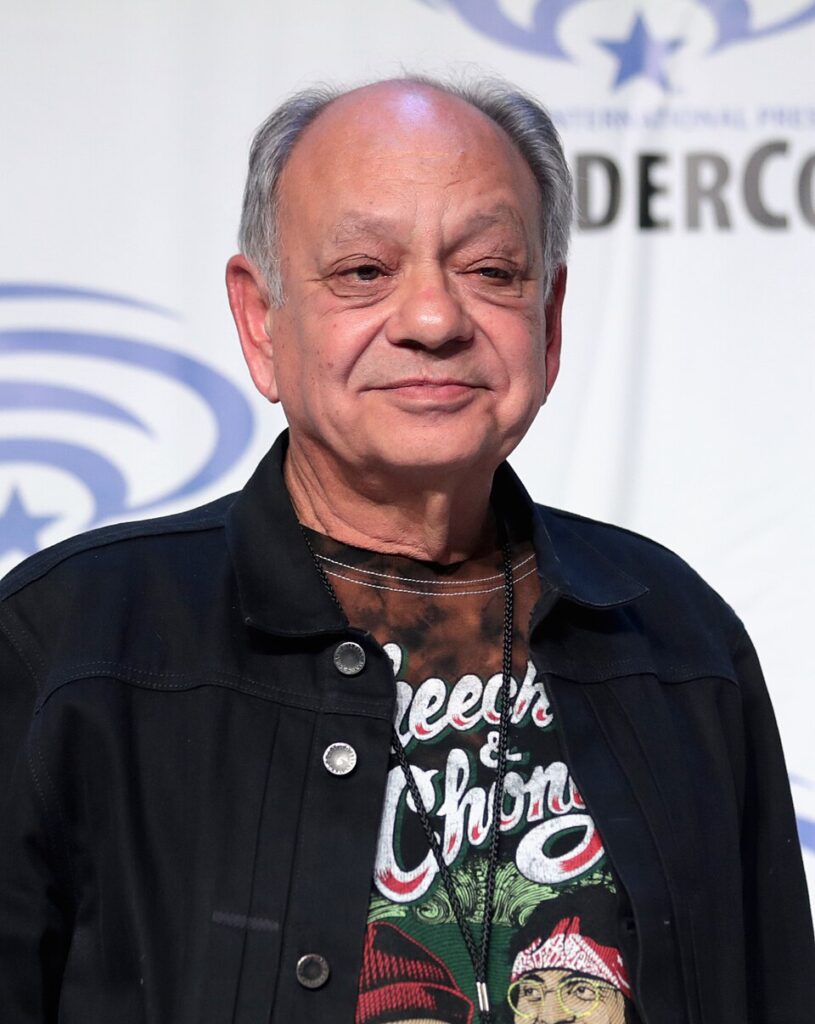

“This country was made by immigrants. It is the one continuing fact of our existence in the United States; it is made and serviced and projected by immigrants,” said actor and art collector Cheech Marin. His message to artists is clear: “This is your time. Make art that matters. Make art that addresses,” he urged. “The Chicano art movement started as the face of the civil rights movement… They made the signs, the placards, and the backdrops and the handbills … the artists were in a way leading that first charge.”

The second section features contemporary Texan artists, such as Carlos Donjuan, whose striking piece R-U-Ready presents three mysterious figures wearing animal masks, blurring the lines between playfulness and eeriness.

The exhibition opened just one day after the protests that flooded the country, including Riverside, where demonstrators rallied under the banner of “No Kings Day,” denouncing the Trump Administration’s authoritarian policies and defending immigrant rights.

Marin referenced Frank Romero’s “The Arrest of the Paleteros,” a haunting image of a SWAT team confronting a group of ice cream vendors, as a symbol of absurd state violence against immigrants. “That was a monumental painting,” he said, noting it “pointed out the ridiculousness of the process they were going through. We need the artist to step up… [[to]] cause enlightenment… Chicano art is a very soulful art… it comes from the center of communities.” The piece is on display in the exhibit.

For Margaret Garcia, an experienced Chicana artist with several works in exhibition, the space represents a crucial act of cultural self-definition. “You are empowered when you are able to define who you are,” she said. “This defines who we are. It says, this is our culture. This is our people. Not that stuff you’re looking at on TV with gang members and violence and all that other stuff.”

In the third section—aptly named the “Fire Room”—the works explore the motif of flames, including Three Studies of Palm Trees by Perry Vásquez, evoking both environmental destruction and resilience amid California’s wildfires. For many visitors, the space becomes a site of reflection.

Garcia sees the museum as a cultural engine, not just for artistic visibility but for economic renewal. “This venue… has created a destination in Riverside and changed the economy of the entire city… There are restaurants making money, there are street vendors, and there is more activity. It’s a celebration of life and the things that are good here in this town.”

But she also recognizes the moment’s gravity, indicating that what is happening politically right now is very challenging. “Without vision, people perish. It’s a biblical saying… Artists are the ones that are usually on the forefront of trying to provide what that image will be… It gives us hope. We need hope right now.”

Inside the museum, hope took tangible form. Families strolled past vivid paintings and intricate installations, absorbing stories told in brushstrokes and symbolism. For many, it wasn’t just a visit—it was an act of resistance.

One such visitor was Miriam, who brought her father, Angel, to The Cheech for the first time to celebrate Father’s Day. Still processing the emotional toll of the previous day’s protests in Riverside, she almost didn’t come. But reclaiming joy and cultural pride felt urgent.

“I felt a little uneasy about coming today because of everything that was happening yesterday here in Downtown,” she said in Spanish. “But I’m also looking for moments where we can celebrate our culture. For me, it was important to bring my dad here on Father’s Day to experience the art and also to see all the efforts we’ve led since the Chicano Movement in the 1960s… It makes me feel proud to be in this space.”

For Angel, the moment was fascinating. “I feel very good because it’s the first time I’ve visited a museum,” he said with a smile.

The intergenerational symbolism was palpable: a daughter guiding her father through a living record of Chicano identity, at a time when forces outside threaten to erase or silence it. Their presence, like that of so many others, was a reminder that community is also built in the quiet, intentional choice to show up.

The fourth section transitions to pastels, featuring textured, bold compositions by various artists. Among them is Margaret García’s Red & Blue Bitch con Maguey, a commanding piece presenting fierce creatures in enigmatic solitude. The collection pulses with raw emotion and layered symbolism.

The final section brings the exhibit into three dimensions. Highlights include ¡Mejico Mexico! by Frank Romero and White House by Narsiso Martínez, portraying a view of agricultural Riverside and a farmworker drawn inside a cardboard box for produce.

Marin reflected on the evolving meaning of “Chicano” as both a political and cultural identity. “I think that the term Chicano is being very expansive in this period right now as to what that actually means. It means those Latinos who have planted their flag in this country and have been here for a long time,” he said. “Countries go through these periods. We shall emerge from this, because we always have.”

As families, activists, and artists continue navigating one of the most precarious moments for immigrant communities in recent memory, the art inside The Cheech doesn’t just speak—it shouts, weeps, and dreams. It reminds us that culture is not a luxury, but a necessity. And in this fight, it may just be one of our strongest tools.

The Riverside Art Museum and The Cheech are committed to accessibility by providing free, discounted, and standard admission options. Through the Museums for All program, visitors can receive $1 tickets for up to four people by presenting an ID and an EBT card at the visitor services desk.

With support from the Art Bridge Foundation’s Access for All initiative, the museums also offer free Summer Sundays through September 7, 2025. Tickets can be reserved online or on-site.