On September 6, 1981, the tortured and decapitated body of Santana Chirino Amaya was found in a dump in El Salvador where right-wing death squads frequently left people after killing them. His murder helped spark a movement in the US demanding greater immigrant and refugee rights.

Today, it is also key to understanding the arrest and deportation of Kilmar Abrego Garcia, the Maryland man now languishing in El Salvador’s mega prison.

The civil war in El Salvador began in 1981, shortly after the assassination of Catholic Archbishop Oscar Romero in March 1980 and the rape and assassination of four U.S. churchwomen in December of that same year. After U.S. President Jimmy Carter briefly cut off U.S. military assistance to El Salvador following the churchwomen’s grisly deaths, President Reagan quickly resumed aid, sending the country’s right-wing military leaders $1 million dollars a day throughout his administration, a policy President Bush continued until the war ended in 1992.

The conflict drove hundreds of thousands of Salvadorans (and Guatemalans) to flee for their lives, crossing into the United States where many filed for political asylum. The Reagan Administration routinely denied nearly all these claims, prompting the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)—the forerunner to ICE—to deport all the people they detained back to El Salvador.

The Salvadoran military was often waiting for these people at the airport, where they were captured, tortured, and disappeared or killed like Chirino Amaya. In his case and others, Salvadorans in the United States, along with many allies, resisted, forming organizations like El Rescate, the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador, and others, particularly in the Los Angeles Pico-Union neighborhood (McArthur Park) where many Central American immigrants fled during that era.

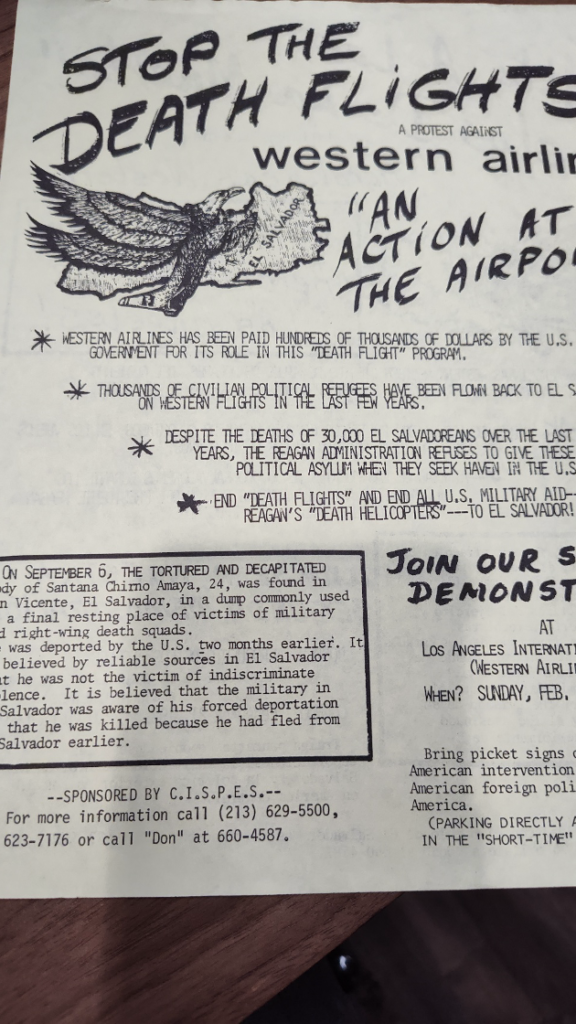

Salvadorans and other progressive activists held protests and rallies, holding signs that read, “Stop Deportation Death Flights to El Salvador” at the Los Angeles Airport. TACA, the Salvadoran National Airlines, along with Western Airlines and Mexicana Airlines, were targeted as they flew Salvadoran migrants back to El Salvador where hundreds were murdered in the early 1980s.

Amnesty International and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) filed reports documenting these killings and the U.S. Embassy in El Salvador and the U.S. State Department examined the matter. Elliot Abrams, then U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs told the Washington Post in 1985, “If those people who go back to El Salvador are killed, as the activists maintain, we’d simply change our policy. But that is not true… it isn’t happening.”

Truth, it seems, is a rare commodity when it comes to US policy on Central America.

After the April 14 meeting between President Trump and Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele in the Oval Office, Homeland Security Advisor Stephen Miller implied without evidence that Abrego Garcia, who migrated to the United States after he and his family were targeted by Salvadoran gangs in San Salvador, was a member of MS-13.

The notoriously violent gang in fact emerged in the United States, more specifically in Los Angeles in the early 1980s, formed by Salvadorans who had been denied political asylum and faced limited economic opportunities here. By the war’s end, MS-13 members began to be deported back to El Salvador, where the organization grew rapidly, extending into Central America, Mexico, and the United States.

It should be noted that after the peace agreements were signed, the U.S. did very little to generate economic growth within El Salvador other than creating free trade zones that U.S. apparel companies took advantage of by establishing maquiladora factories that paid mostly young women extremely low wages, banning nearly all forms of labor organizing and resistance.

There was no Marshall Plan for Central America as there was in Europe after World War II.

El Salvador, Guatemala, and Nicaragua instead experienced extreme economic and political violence throughout the final decades of the 20th and into the 21st Century. Yet U.S. policymakers largely ignored these crises. When they were mentioned, it was mostly within the context of gangs, drugs, and migration.

Days after Trump’s meeting with Bukele, Miller again referred to migrants like Abrego Garcia as “invaders,” language the administration has employed to justify its deportation campaign and the denial of due process to hundreds who have disappeared behind El Salvador’s prison walls.

The United States, of course, invaded Mexico during the U.S.-Mexico War in 1846 and we invaded multiple countries in Latin America in the 19th and 20th centuries. Our government supported a coup against a democratically elected government in Honduras as recently as 2009.

Very few people in the United States know about our involvement, our invasions, our bloody actions in Latin America. Given President Trump’s literal attack on history under the guise of eradicating “wokeness,” many of these stories are now being erased.

Abrego Garcia has been separated from his family, his wife and children, and his home, in Maryland. He came here because we—the United States—devastated his native birthplace.

His journey, much like that of Chirino Amaya, is linked to what Puerto Rican journalist Juan Gonalez, in his seminal 2011 book of the same title, famously called the “harvest of empire.”

Ralph Armbruster Sandoval is professor of Chicana/o Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara.