For voters in North Carolina, it’s like November never ended. That’s because election results for a seat on the state’s Supreme Court have yet to be confirmed, nearly five months and two recounts after ballots were cast.

According to voting rights advocates, that’s the sort of election chaos the country can expect should the plaintiffs in the case prevail.

“This is a test case,” says Ann Webb, policy director with the non-profit Common Cause North Carolina, that would “green light the idea that it is okay for candidates and courts to change the rules that apply to elections after the election has passed.”

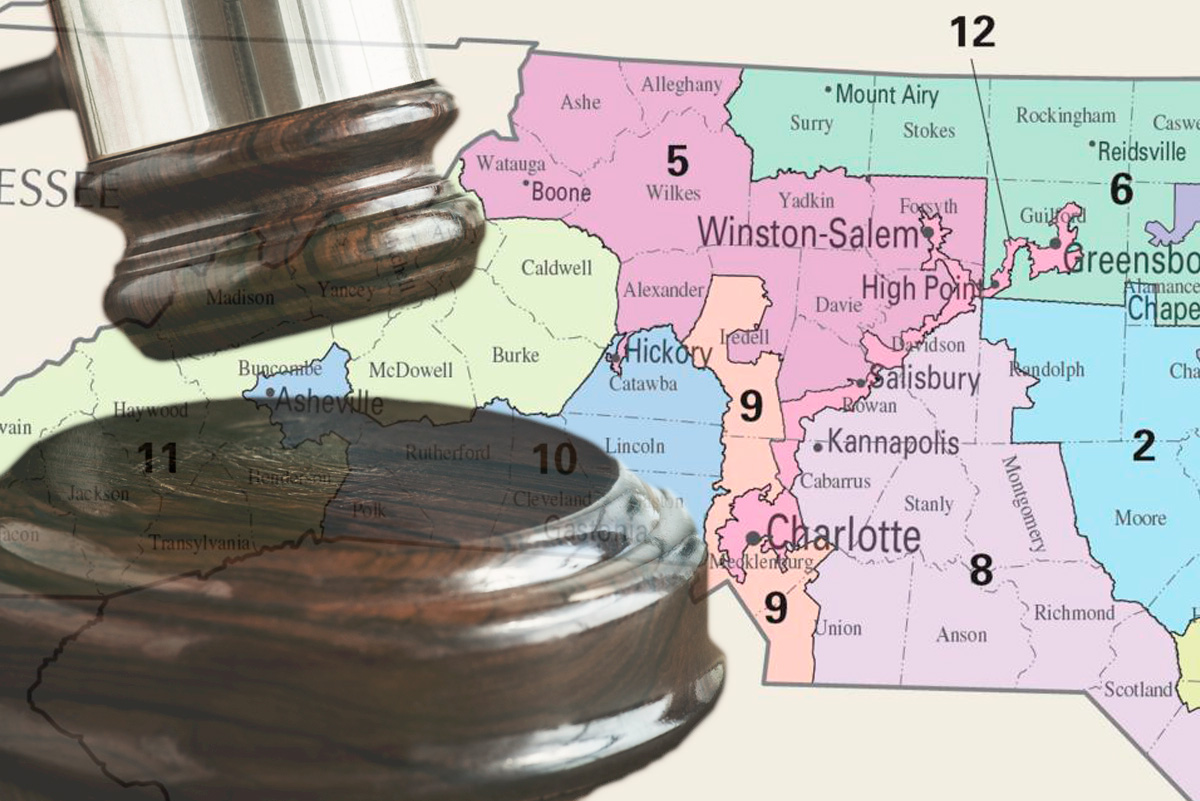

Two weeks after losing his race by 734 votes, Republican candidate Jefferson Griffin sued the state’s Board of Elections, seeking to throw out more than 65,000 ballots, most of them in Democratic leaning districts.

Griffin’s opponent in the race, incumbent North Carolina Supreme Court Justice Allison Riggs, has called the effort an “unprecedented threat to democracy” and vowed in a social media post to continue “fighting for every eligible North Carolinian’s right to vote.”

In his suit, Griffin claims voters failed to provide required identification at the time they voted. North Carolina requires voters to provide a driver’s license or the last four digits of their social security number. Griffin also argues voters who were born and are still living outside the US—for example children of members of the military or missionaries abroad—should not have the right to vote.

Investigations have found that many of the irregularities cited by Griffin were the result of administrative error and therefore not the fault of voters, and that overseas voters followed existing rules in place at the time they cast their ballots.

Critics of the suit also contend that no similar concerns were raised over votes cast in national races, including for the White House. Donald Trump won North Carolina by just over 3%.

Two recounts also confirmed Rigg’s narrow victory.

Still, last week a Republican-led state appeals court sided with Griffin, ordering voters to “cure” their ballots by verifying or correcting their registration information. In their ruling the judges wrote, “The inclusion of even one unlawful ballot in a vote total dilutes the lawful votes and ‘effectively ‘disenfranchises’ lawful voters.”

Those effected by the decision—including Rigg’s own parents, who told reporters they’ve voted “successfully” for the past 50 years—were given 15 days or risk having their ballots thrown out.

On Monday the North Carolina Supreme Court stepped in, blocking for now the lower court’s ruling following an appeal from Riggs and the State Board of Elections. As a member of the court, Riggs has recused herself from the case, leaving the state’s high court with five Republicans and one Democrat. The justices will now review the lower court’s decision.

“Depending on the outcome, there will be multiple attempts to take the case to federal court and try to stop the stealing of these votes,” says Webb, noting the case “opens opportunities for any candidate who has a close election to try to disrupt and drag out finalizing the results.”

The Brennan Center for Justice, which filed an amicus brief on behalf of affected overseas voters, issued a similar warning, saying that the rejection of more than 60,000 votes “would create chaos for our system of democracy, incentivizing future candidates to bring similar post-election litigation seeking to overturn their loss.”

In March, more than 200 senior state government officials, lawyers, and legal educators issued a joint statement pressing Griffin to drop his suit, which they described as “a threat to the public’s faith in our judicial system.”

The case in North Carolina is part of a broader political battle over voting rights. On April 10 the House passed a bill, the SAVE Act, that requires voters to present either a passport or birth certificate when casting a ballot. Numerous groups have come out against the bill, describing it as a direct threat to “voters and democracy.”

A pending case before the US Supreme Court out of Louisiana, meanwhile, could further undo the landmark Voting Rights Act, posing serious implications for voters of color across the country.

North Carolinians, meanwhile, are incensed, says Webb.

“We are hearing from voters. We are getting lots of calls from voters who are so angry that anyone would dare accuse them of not being registered or not following the rules,” she noted.

She added, “This has crossed a bridge with many voters we’ve spoken to. North Carolinians are going to pay a lot closer attention to future judicial races.”