Every so often you encounter a story that opens doors and opens imaginations onto previously unimagined or unrecalled realities, to the way things were or might have been, and things that still can be. If only by sheer dint of will.

It’s that power inherent in story that so rattles authoritarians, who seek to close those same doors, to be the gatekeepers over which doors are opened and which shut.

In the photo there’s a young adult, eyes intent, staring through wire framed glasses, hair closely cropped. The name under the portrait is Mike Chung, and it’s notable because “Mike” is the only Asian in the group of graduating University of Southern California medical school students that year, 1916.

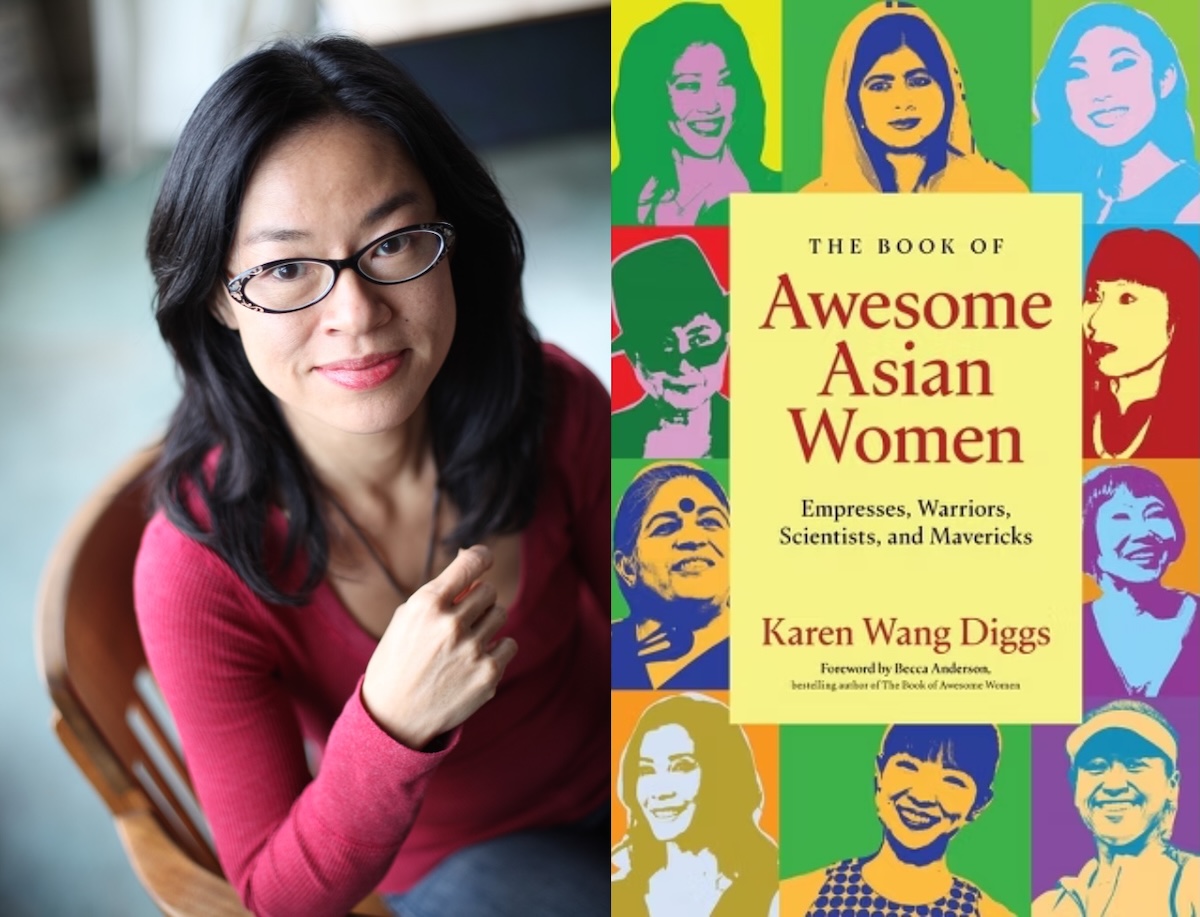

It’s also notable, writes author Karen Wang Diggs in her new book, “The Book of Awesome Asian Women: Empresses, Warriors, Scientists, and Mavericks,” because Mike is not a Mike. She’s Dr. Margaret Chung, whose life and accomplishments could easily fill the pages of a Netflix miniseries screenplay.

The first female American-born Chinese physician, Chung – who was by all accounts lesbian, though she never identified as such – helped found the U.S. Naval Women’s Reserve (WAVES) while recruiting pilots for bombing raids fending off Japan’s pre-WWII invasion of China. That she was wartime pals with the likes of John Wayne and Ronald Reagan, who affectionally called her “mom” and who were part of her “band of fair-haired bastards” that included Amelia Earhart, is barely a footnote in the register of Chung’s achievements.

Why isn’t her name indelibly etched into the annals of American history? Why has her story been allowed to lapse into our collective amnesia? Why wasn’t I taught this in school? It’s not hard to guess at the answer. Just as it’s not hard to appreciate the sheer force of Chung’s story as a parable for her – and our – time.

“This is a book I wish I’d had as a girl,” writes author Becca Anderson – from whose “Book of Awesome Women” comes the name for Diggs’ own work – in the foreword.

The book’s protagonists – past and present – span centuries, ranging from Wu Zetian, China’s first female empress whose rule augured what many consider China’s golden age of the Tang Dynasty, to the 1st Century tale of the Trung Sisters of Vietnam, whose story of resistance inspired soldiers closer to our own time fighting off U.S. forces.

Contemporaries include better known figures like Yoko Ono and Malala Yousafzai to more obscure names like Malaysian astrophysicist Mazlan binti Othman, whose pioneering work brought her country to the stars, and Annette Lu, the former jailed dissident who would climb the rungs to become vice president of Taiwan.

Yet despite their towering successes, for Diggs there’s an intimacy in the telling of these stories, a sense of deep personal reflection, of connection with her own life and the lives of the women around her, specifically one woman.

“She did have bound feet. They were literally like this small,” says Diggs, holding her hands inches apart. “We called her in Chinese ‘dai mor’ which literally identifies her as the wife of my dad’s eldest brother.”

Born and raised in China’s mountainous southern province of Yunnan, Diggs’ aunt, Yang Chat-mei – illiterate to the end of her days, a woman who made her own shoes by boiling rice for glue, layering paper for the soles because there were no shoes available to fit her tortured feet – forms the pillar around which memories of Diggs’ own family and her childhood revolve.

And the inspiration for her latest book.

“She is the prime example of someone who is underappreciated and underrepresented,” says Diggs. “Even my own family didn’t appreciate her, because we never got the story from her.”

That story, of stubborn grace under fire, of stoic resolve and of home cooked meals made from scratch, day in and day out, of her aunt waving goodbye from the steps of the senior center in Hong Kong as Diggs’ family embarked for America, leaving her behind, create a sense of nostalgia for something barely out of reach, something missed.

And an urgency to reclaim it today.

“Something about her spirit and my own maturity… being more cognizant now of a woman’s identity, and what we take for granted,” says Diggs, reflecting on the enduring impact of her aunt’s memory on her life and on her writing.

It’s hard to read these stories without reference to the current moment, one that is in many ways defined by an ongoing pitched battle over what narrative will prevail. As a creature of the media, President Trump knows instinctively what a good story can do. It brought him to the pinnacle of world power.

And with that power, his administration is now seeking to take control of the reins, to determine who belongs and who doesn’t, whose story is told and whose isn’t.

And it’s not just here. Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Hungary’s Victor Orban, China’s Xi Jinping, El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele, to name just a few, men straddling the world stage while imposing some form of revanchist manhood even as they steer us and the planet toward the precipice.

“Colonization trying to reassert itself in the form of a masculine dictator,” is how Diggs describes it.

And the response. “If we listen carefully,” she writes, “we can hear the voices of brilliant females, past and present, beckoning us to be brave and stand up for sovereignty over our destinies.”

May is AAPI Heritage month.

The Book of Awesome Asian Women: Empresses, Warriors, Scientists, and Mavericks | Karen Wang Diggs | Mango Publishing | 268 pp. | Paperback, $22.99