Even without the excellent exhibition catalog essays for “Ruth Asawa: Retrospective,” which opened April 5 at SFMOMA, it is apparent that for Asawa, there was no line between living a full life and making astonishing art, no limits on inspiration, no place that wasn’t a good place for creation and appreciation.

The lines that mattered to Asawa were the ones she liberated from the page when she turned ink sketches into the wire works that she called “continuous form within form” in a practice she described as “like a drawing in space.”

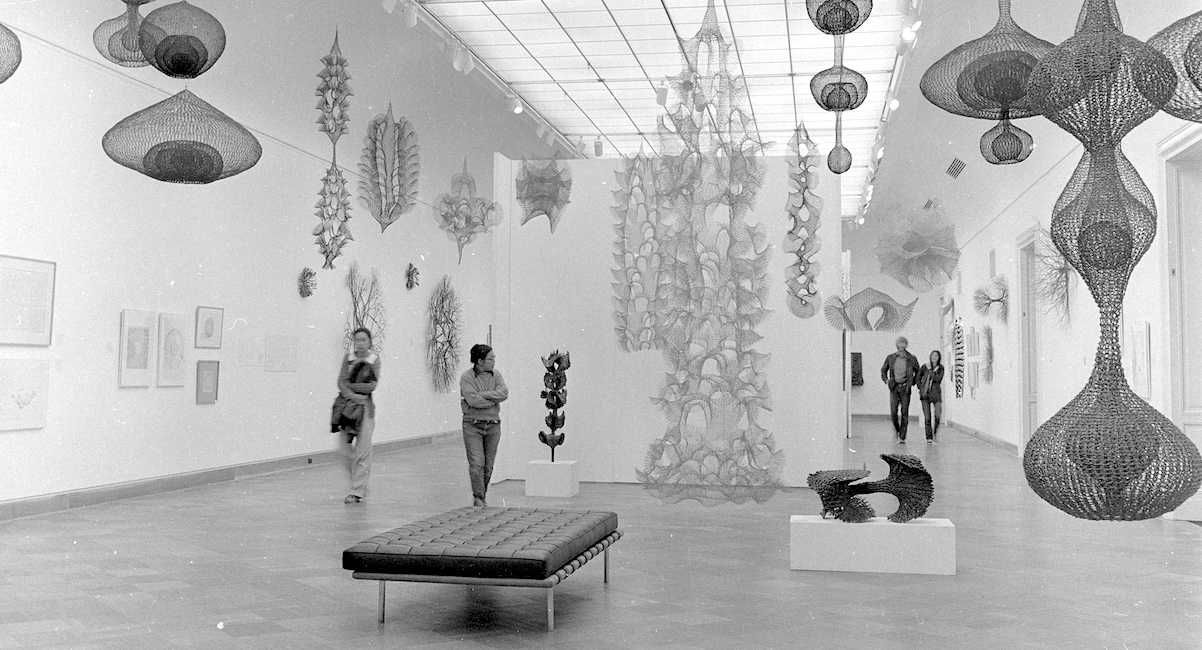

Dozens of her wire works hold pride of place among the 300-plus pieces in the show. These abstract wire works evoke flowers, lanterns, seed pods, birds, chiffon gowns, fantasy creatures from children’s picture books, giant Christmas ornaments and peaceful sea monsters.

From a distance, the pieces with “open forms,” falling petals, “ears” and “tails” appear to be trimmed in eyelash lace. But up close, you can see that those edges are curving back into loops. Take the time to consider the shadows these pieces cast.

So many, many, many lines and loops and layers in wire and ink and paint. Despite the density of detail, Asawa’s lines are light and fluid and often joyful, as in a gorgeous set of flower drawings she made to thank friends who sent her bouquets from their gardens. It’s a pleasure to try to figure out where the lines begin and end.

While Asawa, who died in 2013 at the age of 87, is world-renowned for her wire sculptures, in the Bay Area she may be best known for the public arts high school that bears her name and her weightier public art works, including “Andrea” at Ghirardelli Square, “San Francisco Fountain” at Union Square, “Garden of Remembrance” at San Francisco State University, “Aurora” at the Embarcadero and the Japanese American Internment Memorial in San Jose.

But there is so much more to learn and see and marvel at in the retrospective. The great gift of this exhibition is how it marries the depth and breadth of Asawa’s work to the story of how her approach to life made the art possible.

“How one sees, one does; how one does, one is,” Asawa wrote on an exam as a 20-year-old art student at Black Mountain College in Asheville, North Carolina. The retrospective, co-curated by Janet Bishop of SFMOMA and Cara Manes of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York in collaboration with Asawa’s family and Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc., demonstrates that Asawa’s youthful declaration was consistent throughout her long life and integral to who she was before she ever put it into words.

From her earliest days, Asawa saw ideas and possibilities everywhere. She recalled that as a child on her family’s farm in Southern California, “We used to make patterns in the dirt, hanging our feet off the horse-drawn farm equipment. We made endless hourglass figures that I now see as the forms within the forms in my crocheted wire sculptures.”

Several of Asawa’s pieces, like a drawing of seven Thonet-style chairs, are exercises in finding form in negative space or the beauty in what’s left.

The child of Zen Buddhist Japanese immigrants, she was a teenager during World War II when the U.S. government imprisoned Japanese and Japanese Americans in detention camps.

Despite the misery of losing her home and being separated from her father and a sister, while Asawa and the rest of the family were detained at Santa Anita Racetrack, she relished taking drawing lessons from three Japanese American Disney illustrators who were also being held there. Rather than look back on these experiences with bitterness, Asawa said they made her who she was, and she was “happy” with who she was.

After racist policies kept her from getting a teaching certificate, she traveled to Mexico with her sister and met a woman who told her about Black Mountain College. At this experimental, integrated art school in the mountains of western North Carolina, Asawa studied with Josef Albers, Merce Cunningham and Buckminster Fuller, met her classmate and future husband Albert Lanier and made lifelong artist friends.

During her work study job in the school’s laundry, she made a series of inked patterns using the “BMC” laundry stamp. A page of pinwheeling whorls she stamped around 1948 is echoed in a 1962 ink drawing of a cross-section of a redwood tree. She sold other “BMC” patterns to a company that marketed them (without crediting Asawa) as “Alphabet” wallpaper and textiles.

The exhibition presents more than 300 pieces of Asawa’s work, including cast sculptures, folded paper sculpture, drawings, watercolors, life masks, a suite of 54 lithographs she made in 1965 during a two-month residency at Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles and two nine-foot-tall redwood doors Asawa designed and carved with help from her children.

Visitors are invited to touch a replica of the “Peach March” section of the San Francisco Fountain, a project Asawa made with clay models from 200 San Francisco schoolchildren and additional help from her own kids and her mother Haru.

Asawa rarely titled her work; instead, most of the pieces are identified by technical descriptions, leaving room for the viewer’s imagination.

“Wall-Mounted Electroplated Tied-Wire, Center-Tied Four-Branched Form Based on Nature” (1963) looks like an artisanal dust mop made of pigtailed Afghan hound locs. You know it’s heavy metal, but it looks as if those locs would wave if you could take it off the wall and shake it.

“Freestanding Organic Anemone‐Like Form, ca.1963–65 (electroplated), cast 1972 Patinated bronze” resembles the farmers market cauliflower, with all the spindly green branches topped with tiny cream tufts.

Witchy wreaths and bundles of tied wire branches hang from the ceiling, casting cool shadows that make you think about what’s there and not there. The massing of soft chrysanthemum petals from a 1974 ink sketch echoes the bronze and copper bundles of branches. In 1980, a different chrysanthemum has been cast as a copper foil plaque.

A particularly beguiling patinated 1997 bronze “freestanding stalagmite form” looks like a sea creature made of long, nubbly fronds of blue-green/bronze-brown dinosaur kale waving skyward through water; animal, vegetable and mineral all at once.

In a room designed to resemble the living room of Asawa and Lanier’s Noe Valley house, there’s a 2018 patinated bronze made from a 1976 wax cast of Asawa’s hands. Even though there are photos of Asawa at various ages throughout the show and a catalog photo of her sitting inside of one of the mesh bubbles as she works on it, it is still stunning to think of all she made with those small, strong hands. Even more stunning to realize that she made much of this work while she and Lanier, an architect, were raising six children.

Their oldest daughter, artist Aiko Cuneo, says her mother brought friends and family and art all together in their home. “It was all the same in the house. In the kitchen, sometimes up in the bedroom. In any space in the house; there was only a studio space after 1961, but it was still in the house. It was like she would put the spaghetti pot on and work on a sculpture. Stop and start.”

When she needed uninterrupted time, Cuneo says Asawa would rise at 4 a.m. to have a few hours to herself before the kids got up. “She had this work ethic that was from her parents, who were some of the hardest-working people ever,” she says. “There were seven of them, and they were necessary to keep the truck farm, so she knew how to work hard. She enjoyed working. She taught us to cook and clean and iron and help around the house. My mother didn’t use the word ‘work’ very often; she really wanted us to figure out how to enjoy what you were doing, even if it was cleaning.”

Watching their mother’s works in progress, the Asawa children learned that mistakes are part of creation. Cuneo says her mother told them, “’Try something new. Don’t be afraid to fail. You know if you have an idea, you’ll eventually work that out. You have to have failure in order to get there.’ I think is one of the most important life lessons she taught us.”

Ruth Asawa: Retrospective is on display at the SFMOMA where it will run through Sep. 2, 2025.